Five decades after the election of Allende’s Unidad Popular government, Patricia Espejo Brain, Salvador Allende’s private secretary, publishes her memoirs. She writes about the events and anecdotes of the president’s inner circle, but also about her years of exile and the Resistance Committee that she formed with Tati Allende in Cuba. “The [2019] social uprisings and the crisis the political parties are going through, made me feel that it was necessary to shine a light on the inner workings of the Allende government”, she confesses.

By Victoria Ramírez

Patricia Espejo Brain remembers very clearly the last time she saw General Augusto Pinochet. He was coming out of the Presidential office and walking to the lift with Salvador Allende. It was September 10th 1973, and in the private offices everyone was hard at work. Patricia, who had been at La Moneda since the beginning of the Unidad Popular, recognises that while she’s forgotten a lot things in life, she remembers perfectly those thousand days with Allende. On that occasion the President called her over to say goodbye to the General, who assured Allende that the army would support him “to the bitter end”. With that, he said goodbye and the gates of the elevator closed. Then she and the President –Chicho– his hand on her arm, walked along the corridor, where he turned to her and asked in a low voice, “Will that be the betrayal?”

The book is rich in these intimate moments, plucked from the memories of Patricia Espejo, who was a private secretary and adviser within Salvador Allende’s closest circle that also included her friend and colleague Miria “Payita” Contreras and the President’s daughter Beatriz “Tati” Allende who both worked in the private offices. After 25 years in exile –in Cuba and Venezuela– and a stoical silence about her past, her book Allende inédito. Memorias desde la secretaría privada de La Moneda (“Allende Unpublished. Memories from the Private Officesof La Moneda”, Aguilar) was published in October. A sociologist, Patricia returned to Chile in 2002 and worked for ten years as the Executive Director of the Salvador Allende Foundation. She began writing the book in July 2019, inspired by a promise she had made to her friend Víctor Pey, ex-Director of the newspaper Clarín, but also because she wanted to pass on to younger generations what she had seen. “I couldn’t not tell this story; I’m almost the only one still alive”, she explains calmly over the telephone.

In her memoirs she reveals Allende’s warmth and humanity, his enormous talent as a public speaker, and what he was like as a father and a friend, demystifying him through anecdotes that show his sense of humour and his down-to-earth side. Like the time that one weekend at the house on El Cañaveral he played a trick on General Prats, pretending to fait. Or those days at the Presidential Palace on the Cerro Castillo hill in Viña del Mar during the summer of 1972, when Chicho, wearing a loose-fitting shirt, played host to children who had received excellent grades at school. Or the marathon movie-watching sessions –Westerns– when he’d enjoy two films back-to-back. Or those evenings when, on a whim, Allende would put on his white coat and visit hospitals without telling anyone beforehand. She also writes about his sadness: the deepening isolation in the second year of the government, the disloyalty, the deceptions, the constant tension with the political parties.

The historic events that mark the Unidad Popular government are there: The night that a sea of people listened to the new President speaking to them from the balcony of the FECH (University of Chile Student Federation) building, the day the copper industry was nationalised, the construction of the UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) building, Fidel Castro’s polemical visit to Chile, the negotiations between the parties from the left and right-wing, the coordination of the GAP (Group of Personal Friends), the shortages, the threats made by Patria y Libertad (“Fatherland and Liberty”), the constant changes of cabinet and the myriad other things that happened during those years and that Patricia Espejo witnessed first-hand.

“I’ve always kept a low profile, not only because it’s in my nature, but also because of my beliefs. I wrote the book because history doesn’t say much about what Salvador Allende was like as a person. There’s a lot of enthusiasm nowadays and it’s important to show just how hard it is to govern a country. You’re not only confronted with your closest allies but also with your enemies within. Governing means having lots of qualities, different ways of thinking and behaving, and being able to empathise with what others feel. These are values that have been eroded and nowadays the relationship between a president and the people is distant, and marked by authoritarianism and domination. The social uprisings and the crisis the political parties are going through made me feel that it was necessary to shine a light on the inner workings of the Allende government”.

The private offices were on the second floor of La Moneda, across from the Regional Government Offices and the Plaza de la Moneda, at the crossroads of the streets Moneda and Morandé. Patricia Espejo Brain would arrived first, sometimes at the same time as Allende, when she managed to coordinate with the “Toromanta1”, the car that brought the President from his house in Tomás Moro Street, always protected by members of the GAP. Payita would arrive at ten-thirty and Tati at midday. There were established routines, the doctor –as Patricia called him– had lunch at two o’clock in the big dining room, usually a working lunch. Then he’d sleep a ten-minute siesta on a sofa bed that had been set up in the presidential office. “It was a ritual, he’d put his pyjamas on in the adjoining bathroom, open up the bed and go to sleep”, she says. Over time a connection of trust developed between them: “Because I was never anything more than a colleague, he came to think of me as someone whom he could confide certain secrets in”.

Decades later, during her first government, President Michelle Bachelet asked Patricia to try to rebuild Allende’s presidential office as a sort of homage, but it was impossible. While Pinochet was in power everything had changed. “They changed the physical structure of the place. Perhaps it was a way of forgetting”, she thinks, and comments that even today she finds it uncomfortable going to La Moneda, not only because of the rigid protocol, but also out of nostalgia for the simplicity she no longer finds in the ostentatious public rooms.

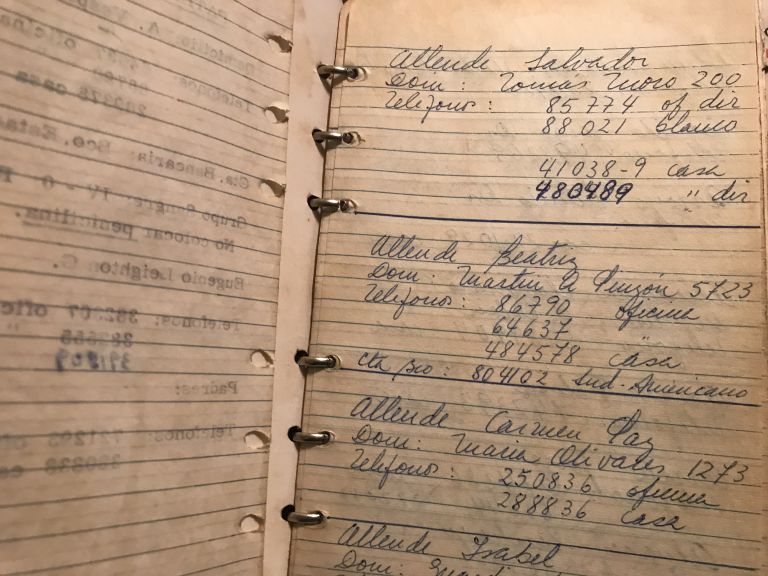

Allende would leave her messages and little gifts on her desk. One of the most memorable was a note he wrote on a day she arrived late, because she’d slept in after looking after her sick daughter all night. The notes said: “Kid: / The clock stopped, it’s nine forty-five, and, oh well/ I feel lonely / Dr Allende”. Funnily enough, Patricia took this scrap of paper across the border with her on the 12th September 1973 when she went into what would be a long exile. Apart from her book of contacts, which would later on prove to be invaluable, it was the only thing she managed to take with her. She didn’t have a suitcase or even a change of clothes, only what she had on.

Disagreement between the parties

Looking back, Patricia believes that some of the political parties in the Unidad Popular coalition had no idea of how to understand the revolutionary and democratic project that Salvador Allende was trying to undertake, or else, in her words “they weren’t up to it”.

“There was so much disagreementbetween one sector and another. The most powerful parties were the Socialist Party and the Communist Party, the latter being probably the most important. The Socialist Party in particular sinned by omission. But on the other hand the MIR (Revolutionary Left Movement) couldn’t understand that it wasn’t possible to govern like they wanted to. Political processes take their time – even if you’re going to expropriate twenty estates you’re not going to solve the problems for the farmers.Allende had to depend more on the opinions of his friends and politicians than on the members of the political parties”.

Although Patricia was a militant in the Young Communists while she studied sociology, and during her exile she was a militant in the MIR until 1976, after that she stopped being a militant. “I’ve never left politics, I stopped being a militant, it’s different”, she states.

“We were naive and thought that the Armed Forces were a coordinated and vertical institution. Nobody imagined it would be possible to bomb La Moneda. The President’s last gesture was to call for a plebiscite on the 11th September, which shows his common sense, his commitment and his loyalty. The President was not going to let a bloodbath take place”.

Returning to Havana

She had been in Havana for three days when she was taught how to shoot. Training started at 6am and finished at 6pm. Then there was time to sightsee and meet up with friends. It was May 1971. “I’m quite short and at the time I was skinny, so I held the AK to my waist to be able to shoot and the kickback was so hard that it made me spin to the right where Blanca was, and I missed her by a hair’s breadth”, she writes in her memoirs. The Blanca she’s writing about is Blanca Mediano, who would also work in the Presidential private offices.

Patricia had seen people waving the Patria y Libertad flags on the streets of Santiago, their armbands and their hostility. She was afraid and when she saw old friends they’d yell “bloody commie” at her. That was the beginning of a journey that took her to Cuba to learn about personal defence and intelligence. “Then you know what precautions to take at home, how you can prepare”, she explains. Her aunt, Paz Espejo, had already been in Cuba for twenty years, having gone there to support the 1959 revolution.

After Allende’s government was overthrown Patricia returned to Cuba, but this time unattached to any party. During those years she would receive other exiles, and with Tati Allende she heard the first accounts of torture. This would also be where she would join the MIR when Jorge “the Trosko” Fuentes –later kidnapped during Operation Condor– would invite her into the organisation on the express wishes of Miguel Enriquez, who passed on a message during a meeting on a boat out to sea.

During the first week after the 11th September coup Patricia and Tati Allende established the Solidarity Resistance Committee in the Chilean embassy in Cuba, which is today known as the Salvador Allende Memorial House. It was a particularly difficult time, coordinating as quickly as possible the escape out of Chile via diplomatic routes for those people in danger, and receiving early direct information about the atrocities of the torture being inflicted. “The violence of those testimonies was almost unbearable”, confesses the writer, as she remembers the first accounts of terror.

“Sometimes when I think about it I wonder how we were able to do what we did. Tati was the strong one. We arrived in Cuba on the 13th and Fidel wasn’t there. We got straight to work, finding as many people as possible with the help of third-party countries. My contact book was invaluable to understand where the focus was, how the military were operating, who was in the greatest danger. Every day we heard of another companion who’d fallen. Immersing ourselves in the work helped us bear the pain, and we received constant support from the [Cuban] revolution”.

Towards the end of 1973 Patricia and Tati wrote the first human rights report and presented it at the UN in a session where Mercedes Hortensia Bussi (“Tencha” – Allende’s wife) was also present. After a while the accounts they were reading took their toll. At one point Patricia broke down and had to stop working. “I was reading an account and I started to laugh hysterically. I decided I had to stop or I’d go crazy”, she explains. She told Tati that they’d have to take care of themselves to avoid getting ill, but Tati felt she had to carry on with the work.

“Tati never got over the fact that she left Chile on the 11th September. The Cubans are very careful about the role everyone plays and she had links to diplomats and other people, so she must have had more information. I think that afterwards the emotional and family side of what happened caught up with her, and destroyed her. She also wanted to get back into medicine and wasn’t allowed to. Then she wanted to go back to Chile and they wouldn’t let her, and she just couldn’t see a way forward. Tati’s death was like the death of a sister. I don’t think she ever got over her father’s death”.

Tati had been a militant in the section of the Socialist Party allied tothe ELN in Bolivia, the “elenos” who supported Che Guevara in the Latin American revolution. Although Tati had close ties to revolutionary groups, she supported the Unidad Popular’s democratic project. “She loved her father deeply, she was his favourite, she anchored him. She respected and admired his tenacity and his commitment to the poor. She knew that the path they’d chosen was difficult and maybe impossible”, remembers Patricia, adding that Tati didn’t give herself the space or the time for tiredness or sadness. Over recent years books have been published focusing on her story, most recently Tati Allende: una revolucionaria olvidada (“Tati Allende: A Forgotten Revolutionary”, 2017) but for a long time she was all but forgotten.

“She’s forgotten because she’s troublesome, she’s a revolutionary who says things as they are, she can fight, she’s critical of the political parties. It would have been incredibly hard for her to live in such a selfish and class-ridden society, because she was, as a person, the complete opposite. She’s not a figure that invites consensus. Nowadays you have to be so much more cautious and acquiescent; you have to forget that the Christian Democrats made our life impossible. All sorts of things that Tati wouldn’t have done. She was an extraordinarily affectionate woman, always very understated, always very hard on herself”.

After Tati’s death Patricia maintained her links to the Allende family. She became very close to Tencha, and in her later work at the Salvador Allende Foundation she tried to draw attention to the work of Allende’s government and of those who accompanied him to the end. One year after the social uprising, she has no doubt about Allende’s legacy and the current political processes.

“I believe that his legacy is political coherence. During those one thousand days that he governed he was committed to his people, including the political parties that didn’t always support him. The social uprising of today shows us just how abnormal the social differences are. There’s corruption at every level and the people have had enough of politicians. What really struck me about the uprising last October 18th is that there wasn’t a single party flag to be seen. What I did see, from a distance, two or three blocks from the Plaza Italia, is a flag with Allende’s face on it”.